There’s an old story about a group of blind men who lived in a village. One day someone from the village shouted “holy smokes there’s an elephant in the village!” Elephant sightings are rare and the whole village was all aflutter: “look! look! look! look! look!”

Not to be left out, the blind men, who had zero experience with elephants, said to themselves “even though we can’t see this thing let’s go touch it and figure out what all the commotion is about.”

So they walked up to the elephant and, one-by-one, put their hands on it.

“Oh! An elephant is like a big warm tree trunk!” said the blind man with his hands wrapped around the elephant’s leg.

“Not at all! An elephant is like a rope!” said the blind man who was grabbing hold of the tail.

“I have no idea what you guys are talking about. An elephant is like a big flappy fan,” said the blind man with his hands on the ear.

“I guess ‘elephant’ is just another word for ‘wall?’” said the blind man as he pushed against the elephant’s side.

“Ooh an elephant is like a piece of bamboo!” said the blind man with his hands on the tusk.

“AHHHH! IT’S LIKE A SNAKE!” said the blind man with his hands on the trunk.

And so they argued and argued about what an elephant was like until the elephant became so annoyed that he sat on them and squished them flat.

The end.

SEEING THE WHOLE

We are simple little creatures with simple little minds living in an increasingly complex world. It’s easy, and almost natural, to see the world as a jumble of individual parts rather than as a series of interconnected systems. In order to really understand those systems, we need to be able to not just see the individual parts, but understand how they connect and interact to create a whole that is larger than the sum. Systems thinking is seeing the world as an interdependent whole that is constantly in motion.

WHAT IS A SYSTEM?

A system is a set of connected and interacting parts that form an integrated and more complex whole. This pile of disconnected parts - a hose, a bathtub, and a plug - are not a system. They are individual parts that do not interact:

Stitch them together, and you have a system:

If you add or take away anything from this system you will change the whole.

WHAT IS SYSTEMS THINKING?

Systems thinkers use models to create a more whole, accurate, and manageable picture of complex and interconnected challenges.

For example: A non-systems thinker who is wondering “why am I tired all the time?" might decide to drink more coffee for a boost in energy.

In contrast, a systems thinker might list all of the factors involved in their tiredness, map out how coffee affects their energy and their sleep, realize that coffee keeps them awake at night, and decide to cut caffeine out of their lives entirely so they can get back to a normal night’s sleep and feel rested again.

The examples above are simple for explanations sake, but every day we deal with challenges of much greater complexity. I spent years working with financial institutions designing products that operate within a complex system of the economy, emotions, life events, technology, market trends, and so on.

But during that time, I realized how easy it is to take an over-simplified cause-and-effect approach to diagnosing a problem:

Like: “Our new mobile platform isn’t catching on, so we’re going to pull resources out of mobile.”

Or: “Our department’s employees aren’t adopting [technology X] so we’re going to cut our new technology budget and try something else.”

You can insert your own example here: _______________________________________

Nothing is as simple as cause and effect, and systems thinking allows you to creatively examine non-linear complex problems as a whole while also giving you the ability to examine each interacting cog.

SYSTEMS THINKING: A METHOD

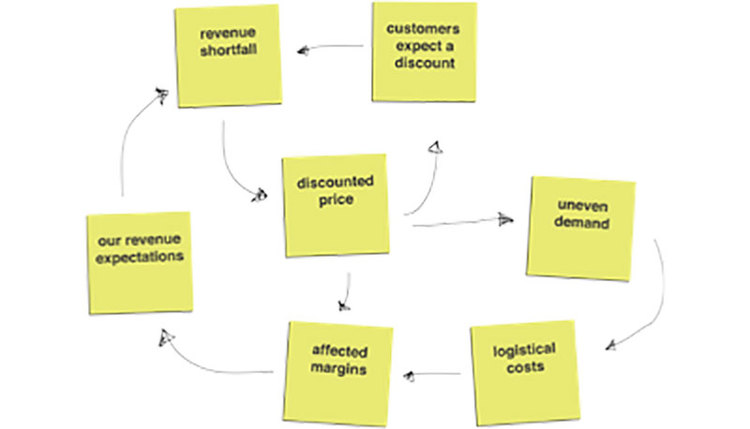

Let’s use an example on sales and profitability from a manufacturing company who finds themselves in a price-discounting free-fall in order to maintain sales volume (example via moresteam.com). Note: We’re going to use a private sector example for now, because it’s handy and available. But, as we go, think about a parallel story in the government or NGO world.

First, let’s identify the events surrounding the problem.

In this case:

- Your sales are below expectations, and

- Your profits are miserable and dwindling

Next, we’re going to visualize this problem as a systems diagram. A visual map allows you to take a problem that might appear one way at first glance and spread it out in front of you so you can clearly see how all of its parts relate and interact.

Grab some post-it notes and make a list on the wall of everything that is affecting this problem. In this case:

After you’ve listed all of the factors playing into your problem, visually map out their relationships. If you aren’t sure of where to start, take a cue from John Coltrane who said “start in the middle and move in both directions at once.”

At this point, we know our customers expectations of low, discounted prices is pushing our revenue down:

…which has created a cycle that leads to continued discounts revenue drops that reinforce those expectations:

This is playing hell on our margins, putting more pressure on our revenue expectations and exacerbating our revenue shortfall:

Meanwhile, the discounted pricing is resulting in uneven demand, which raises our logistical costs to manage, cutting into our margins even worse!

At this point, you have a clear picture of the problem.

This allows you to zoom in and identify the parts you can and cannot control. The big-picture vision of the problem can be especially effective at breaking short-sighted mental models that inflame the cycle.

So, the VP of Marketing who might be thinking “I am focused on sales growth, logistical costs are not my problem” can see that the two are deeply related and react accordingly.

The regional manager focused on meeting her monthly target at all costs can see that her commitment to this cycle will put the company out of business, and react accordingly.

A systems approach allows an organization to solve complex problems from the same vantage point and speaking the same language.

Again, I’ve given this through a private sector business lens, because I want to write this in short order based on existing examples, but I bet you can begin to construct a similar example in governmental and NGO environments.

In fact: I’d love your thoughts on how you see this fitting in our specific UN universe.

Good Habits

Systems thinking is an exercise and method, but has the most impact when it becomes habitual. Habits that will set us down the right path include:

- Seek to understand the big picture

- Observe patterns and trends in the system over time

- Recognize that a system’s structure generates its behavior

- Consider an issue fully and resists the urge to come to a quick conclusion

- Consider how mental models affect your reality

- Look for leverage points that can change the system

- Examine unintended consequences

- Surface and test your assumptions asap

Source: Waters Foundation, Habits of a Systems Thinker (PDF)

Dive In

What now? Get out from behind the computer and try this: Sit down and identify a complex problem in your life. Something that feels unwieldy and difficult to get your hands around, either business or personal. What are all of the parts of the problem? Get them down on paper. Map out how they interact and affect each other. Based on that map, what can you affect? What can you not? Identify the points of leverage and break that system.

What are the most critical complex challenges we should be mapping for our scope in the UN right now?

Let’s Adapt

Let’s find a time to work together and create an example to replace the above. Something that will be directly relevant and relatable to UN employees.

Learn More

To dig deeper, watch this talk on Simplifying Complexity:

And pick up a copy of “Thinking in Systems” by Donella Meadows.

.svg)